1 Abstract¶

This technote reassesses the authentication and authorization needs for the Science Platform in light of early operational experience and Data Facility developments, discusses trade-offs between possible implementation strategies, and proposes a modified design based on opaque bearer tokens and a separate authorization and user metadata service.

This is not a risk assessment, nor is it a detailed technical specification. Those topics will be covered in subsequent documents.

2 Motivation¶

At the time of writing (mid-2020), we are operating a functional but not feature-complete Science Platform service in the Data Facility at NCSA for internal project use and in support of early community engagement activities (Stack Club, for example). This service includes a functional Authentication and Authorization (A&A) service designed by the Data Management Architecture team. This service operates as a layer on top of services, security models, system capabilities, and infrastructure constraints provided by NCSA. We are motivated to revisit some aspects of the design and implementation of our A&A strategy in the light of the following developments:

Early operational experience has highlighted some engineering and usability pain points with the current approach that are ripe for optimization, such as the complexity of juggling multiple types of tokens.

Some existing decisions were driven by pragmatic requirements to integrate with existing NCSA services, such as the University of Illinois LDAP service, and other infrastructure constraints. For example, currently Science Platform accounts must also be NCSA accounts in order to integrate with NCSA-provided storage services. We are now more driven by the need for the Science Platform deployment to be well-separated from the specifics of the underlying infrastructure in order to support a smooth transition to a different Data Facility provider, possibly via an interim Data Facility for Early Operations.

We have had an emerging requirement to provide additional (albeit partial) Science Platform production deployments, such as at the Summit facility. Those deployments will need to integrate with different infrastructure and will have additional connectivity constraints, such as supporting authentication and authorization during an interruption of the external network and providing authentication for the Engineering Facilities Database APIs.

The addition of a Security Architect to the SQuaRE Team and its Ops-Era counterpart have afforded us the opportunity to consider some options that previously would have been ruled out by lack of suitable engineering effort to design and implement them.

3 Problem statement¶

The Science Platform consists of a Notebook Aspect and a Portal Aspect accessible via a web browser, APIs accessible programmatically, and supporting services underlying those components such as user home directories and shared file system space. Science platform users will come from a variety of participating institutions and may be located anywhere on the Internet. Primary user authentication will be federated and thus delegated to the user’s member institution.

The following authentication use cases must be supported:

Initial user authentication via federated authentication by their home institution, using a web browser.

New account creation must depend on the user’s institutional affiliation. Some users (such as non-US users) will require manual approval.

Initial user authentication via a local OpenID Connect service for the Summit Facility deployment.

Ongoing web browser authentication while the user interacts with the notebook or Portal Aspects.

Authentication of API calls from programs running on the user’s local system to services provided by the Science Platform.

Authentication to API services from the user’s local system using HTTP Basic, as a fallback for legacy software that only understands that authentication mechanism.

Authentication of API calls from the Notebook Aspect to other services within the Science Platform.

Authentication of API calls from the Portal Aspect to other services within the Science Platform.

Authentication and access control for sharing data files with user-defined groups of collaborators. The shared files must be accessible from the local system, the Notebook Aspect, and the Portal Aspect of any collaborator. The current project design uses a POSIX file system with a WebDAV access layer on top, relying on WebDAV as the access mechanism from the user’s local system and the Portal Aspect.

Authentication of some mechanism for users to share, copy, and programmatically access files from their local system into the user home directories and shared file systems used by the notebook and Portal Aspects. The current project design requirements call for WebDAV to be this mechanism.

API services within the Science Platform will generally be IVOA Virtual Observatory services, but there may be others that go beyond the VO standards.

We want to enforce the following authorization boundaries:

Limit access to the web interface (the notebook and Portal Aspects) to authorized project users.

Limit access to some classes of data to only users authorized to access that data.

Limit access to administrative and maintenance interfaces to project employees.

Limit access to home directories to the user who owns the home directory and platform administrators.

Limit access to shared collaborative file systems to the users authorized by the owner of the space. This in turn implies a self-serve group system so that users can create ad hoc groups and use them to share files with specific collaborators.

Limit user access according to various quotas (CPU, query volume, storage capacity, etc.).

Users can create long-lived tokens for API access.

4 Proposed design¶

This is a proposed design for authentication and authorization that meets the above requirements. All aspects of this design are discussed in more detail in 5 Design discussion, including alternatives and trade-offs.

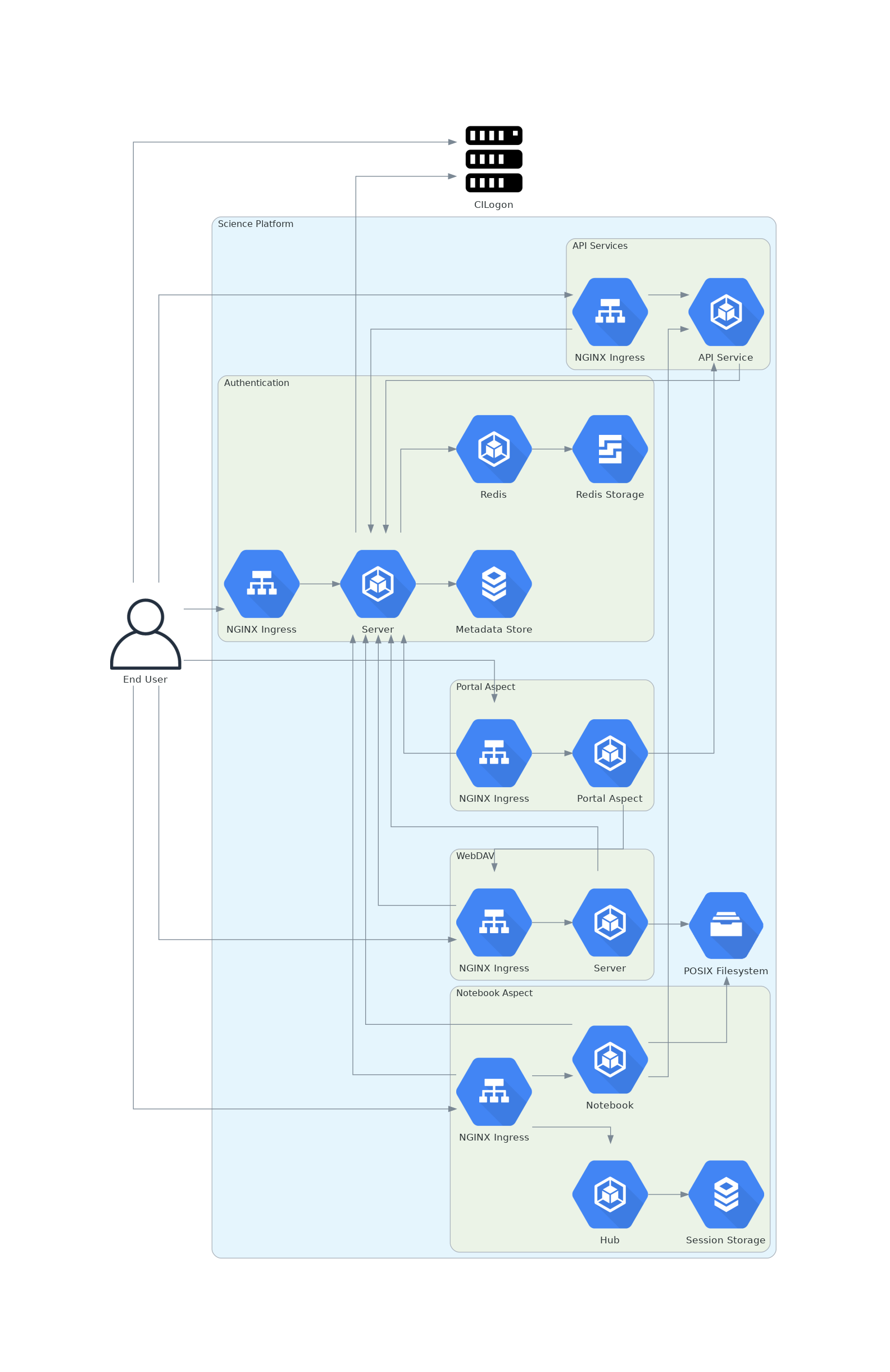

Figure 1 Science Platform architecture¶

This is a high-level description of the design to inform discussion. Specific details (choices of encryption protocols, cookie formats, session storage schemas, and so forth) will be spelled out in subsequent documents if this proposal is adopted.

As a general design point affecting every design area, TLS is required for all traffic between the user and the Science Platform. Communications internal to the Science Platform need not use TLS provided that they happen only on a restricted private network specific to the Science Platform deployment.

4.1 Initial user authentication¶

Initial user authentication for most deployments will be done via CILogon using a web browser. CILogon will be used as an OpenID Connect provider, so the output from that authentication process will be a JWT issued by CILogon and containing the user’s identity information.

If the user has not previously been seen, they may or may not be able to automatically create a Science Platform account, depending on their institutional affiliation. Users affiliated with a US institution will be able to automatically create their account based on their affiliation as released by the InCommon federation via CILogon. Other users should be able to record enough information to allow the project to contact them (name and email, for example), and then be held for manual review and approval. The details of this approval flow will be fleshed out in later documents. See LSE-279 for a general discussion of authentication and authorization for Rubin Observatory.

Once the user’s account has been created, the CILogon-provided identity will be mapped to a Science Platform account. Users will be able to associate multiple CILogon identities with the same Science Platform account. For example, a user may wish to sometimes authenticate using GitHub as an identity provider and at other times use the authentication system of their home institution. They will be able to map both authentication paths to the same account and thus the same access, home directory, and permissions.

Additional metadata about the user (full name, UID, contact email address, GitHub identity if any) will be stored by the Science Platform and associated with those CILogon identities. The UID will be assigned internally rather than reusing a UID provided by CILogon. Other attributes may be initially seeded from CILogon information, but the user will then be able to change them as they wish.

After CILogon authentication, the Science Platform will create a session for that user in Redis and set a cookie pointing to that session. The cookie and session will be used for further web authentication from that browser. Each deployment of the Science Platform will use separate sessions and session keys, and thus require separate web browser authentication.

For the Summit deployment, a local OpenID Connect provider will be used instead of CILogon, but the remainder of the initial authentication flow will be the same.

Administrators of the Science Platform will need a separate interface to the user database to freeze or delete users and to view and fix user metadata.

4.2 API authentication¶

API calls are authenticated with opaque bearer tokens, by default via the HTTP Bearer authentication mechanism.

To allow use of legacy software that only supports HTTP Basic authentication, they may also be used as the username or password field of an HTTP Basic Authorization header.

All services protected by authentication will use an authentication handler that verifies authorization and then provides any relevant details of the authentication to the service in extra HTTP headers. Group membership will be determined dynamically on each request (although possibly cached for a short period of time). See 4.3 Group membership for more details on group management.

Users can list their bearer tokens, create new ones, or delete them. User-created bearer tokens do not expire. Administrators can invalidate them if necessary (such as for security reasons).

API tokens have scopes of access. When creating a new API token, the user can restrict it to a specific purpose. The token will then not be authorized to make calls to other services. Some services, such as token creation and user metadata changes, may not allow API token authentication and require authentication via a web browser. The available APIs, and thus the details of what scopes will be needed and how the user will chose the desired scope, are not yet finalized and will be discussed in a future document.

4.3 Group membership¶

Users will have group memberships, which will be used for access control and (depending on the storage platform) may be used to populate GID information. Some group information may be based on the user’s institutional affiliation. Other groups will be self-service. Users can create groups and add other users to those groups as they wish. All groups will be assigned a unique GID for use within shared storage, assuming we use a storage backend that uses GIDs.

Group membership will not be encoded in the token or the user’s web session. Instead, all Science Platform services will have access to a web service that, given a user’s identity or a scoped token, will return authorization information and group membership for that user or token. For services that only need simple authorization checks, this can optionally be done by the authentication handler that sits in front of the service.

4.4 Quotas¶

User quotas may vary based on their group memberships (which in turn will vary based on their affiliations). The quotas will be part of the data about a user that Rubin Science Platform services can request from the user metadata service. Each service is then responsible for enforcing its own quotas. Services will need to report on current usage and warn if the user is close to reaching their quota, but the design of that system is beyond the scope of this document.

For file storage, quotas may be tied to groups (GIDs) rather than users (UIDs) for shared storage. In this case, the quota would be part of the metadata of the group, and queriable from the group membership web service.

Quotas will require an administrative UI to edit quotas assigned to groups, grant or revoke additional user quota, configure quotas granted based on affiliation, and so forth.

4.5 File storage¶

There are three primary use cases for file storage:

Upload and download tools, configuration, and data to a user’s personal workspace, primarily for the Notebook Aspect.

Share data sets between the Portal Aspect and the Notebook Aspect and download data sets to a local device.

Share data sets with collaborators.

The three use cases need not necessarily be satisfied by the same system, but they are in the current design. It is not yet clear now the VOSpace service will fit into this picture, although it will likely play a role in the third use case.

Users of the Notebook Aspect will have a personal home directory and access to shared file space. In the current design, to support the second use case, users will also have access to shared file space and may create collaboration directories and limit access to groups, either platform-maintained groups or user-managed groups. These file systems will be exposed inside the Notebook Aspect as POSIX directory structures using POSIX groups for access control. The backend storage will be NFS.

To support this, the Notebook Aspect will, on notebook launch, retrieve the user’s UID and their group memberships, including GIDs, from a metadata service and use that information to set file system permissions and POSIX credentials inside the notebook container appropriately.

Users will also want to easily copy files from their local system into file storage accessible by the Notebook Aspect, ideally via some implicit sync or shared file system that does not require an explicit copy command. The exact mechanism for doing this is still to be determined. One likely possibility is a server on the Science Platform side that accepts user credentials and then performs file operations with appropriate permissions as determined by the user’s group membership by assuming the user’s UID and GIDs. In this case, user authentication for remote file system operations will be via the same access token as remote API calls. See 4.2 API authentication.

4.6 Division of responsibilities¶

CILogon provides:

Federated authentication exposed via OpenID Connect

The Rubin Data Facility (including additional and/or interim Data Facilities) provide:

The Kubernetes platform on which the Science Platform runs

Load balancing and IP allocation for web and API endpoints

PostgreSQL database for internal storage of authentication and authorization data

Object storage

Persistent backing storage for supplemental authentication and authorization data stores (such as Redis)

NFS for file system storage

Backup and restore facilities for all persistent data storage

Rubin Observatory Science Quality and Reliability Engineering and its Ops-Era Successor provides:

Kubernetes ingress

TLS certificates for public-facing web services

- The authentication handler, encompassing

OpenID Connect relying party that integrates with CILogon

Web browser flow for login and logout

Authentication and authorization subrequest handler

- User metadata service, encompassing

User metadata (full name, email, GitHub account)

UID allocation

API for internal services to retrieve metadata for a user

- Group service, encompassing

Automatic group enrollment and removal based on affiliation

Web interface of self-service group management

GID allocation

API for internal services to retrieve group membership for a user

5 Design discussion¶

5.1 Initial authentication¶

The Science Platform must support federated user authentication via SAML and ideally should support other common authentication methods such as OAuth 2.0 (GitHub) and OpenID Connect (Google). Running a SAML Discovery Service and integrating with the various authentication federations is complex and requires significant ongoing work. CILogon already provides excellent integration with the necessary authentication federations, GitHub, and Google, and exposes the results via OpenID Connect.

The identity returned by CILogon will depend on the user’s choice of authentication provider. To support the same user authenticating via multiple providers, the authentication service will need to maintain a list of IdP and identity pairs that map to the same local identity. Users would be able to maintain this information using an approach like the following:

On first authentication to the Science Platform, the user would choose a local username. This username would be associated with the

subclaim returned by CILogon.If the user wished to add a new authentication mechanism, they would first go to an authenticated page at the Science Platform using their existing authentication method. Then, they would select from the available identity providers supported by CILogon. The Science Platform would then redirect them to CILogon with the desired provider selected, and upon return with successful authentication, link the new

subclaim with their existing account.

The decision of whether to automatically create a new user account or hold the account for approval will be made based on InCommon metadata (or the absence of it) provided by CILogon as part of the initial authentication. For users who are held for approval, there will need to be some form of delegated approval process, the details of which are left for a future document to discuss.

5.2 API authentication¶

5.2.1 Token format¶

There are four widely-deployed choices for API authentication:

HTTP Basic with username and password

Opaque bearer tokens

JWTs

Client TLS certificates

The first two are roughly equivalent except that HTTP Basic imposes more length restrictions on the authenticator, triggers browser prompting behavior, and has been replaced by bearer token authentication in general best practices for web services. Client TLS certificates provide the best security since they are not vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks, but are more awkward to manage on the client side and cannot be easily cut-and-pasted. Client TLS certificates also cannot be used in HTTP Basic fallback situations with software that only supports that authentication mechanism.

Opaque bearer tokens and JWTs are therefore the most appealing. The same token can then be used via HTTP Basic as a fallback for some legacy software that only understands that authentication mechanism.

JWTs are standardized and widely supported by both third-party software and by libraries and other tools, and do not inherently require a backing data store since they contain their own verification information.

However, JWTs are necessarily long.

An absolutely minimal JWT (only a sub claim with a single-character identity) using the ES256 algorithm to minimize the signature size is 181 octets.

With a reasonable set of claims for best-practice usage (aud, iss, iat, exp, sub, jti, and scope), again using the ES256 algorithm, a JWT containing only identity and scope information and no additional metadata is around 450 octets.

Length matters because HTTP requests have to pass through various clients, libraries, gateways, and web servers, many of which impose limits on HTTP header length, either in aggregate or for individual headers.

Multiple services often share the same cookie namespace and compete for those limited resources.

The constraints become more severe when supporting HTTP Basic.

The username and password fields of the HTTP Basic Authorization header are often limited to 256 octets, and some software imposes limits as small as 64 octets under the assumption that these fields only need to hold traditional, short usernames and passwords.

Even minimal JWTs are therefore dangerously long, and best-practice JWTs are too long to use with HTTP Basic authentication.

Opaque bearer tokens avoid this problem. An opaque token need only be long enough to defeat brute force searches, for which 128 bits of randomness are sufficient. For various implementation reasons it is often desirable to have a random token ID and a separate random secret and to add a standard prefix to all opaque tokens, but even with this taken into account, a token with a four-octet identifying prefix and two 128-bit random segments, encoded in URL-safe base64 encoding, is only 49 octets.

The HTTP Basic requirement only applies to the request from the user to the authentication gateway for the Science Platform. The length constraints similarly matter primarily for the HTTP Basic requirement and for authentication from web browsers, which may have a multitude of cookies and other necessary headers. It would therefore be possible to use JWTs inside the Science Platform and only use opaque tokens outside. However, this adds complexity by creating multiple token systems. It would also be harder to revoke specific JWTs should that be necessary for security reasons. A single token mechanism based on opaque bearer tokens that map to a corresponding session stored in a persistent data store achieves the authentication goals with a minimum of complexity.

This choice forgoes the following advantages of using JWTs internally:

Some third-party services may consume JWTs directly and expect to be able to validate them.

If a user API call sets off a cascade of numerous internal API calls, avoiding the need to consult a data store to validate opaque tokens could improve performance. JWTs can be verified directly without needing any state other than the (relatively unchanging) public signing key.

JWTs are apparently becoming the standard protocol for API web authentication. Preserving a JWT component to the Science Platform will allow us to interoperate with future services, possibly outside the Science Platform, that require JWT-based authentication. It also preserves the option to drop opaque bearer tokens entirely if the header length and HTTP Basic requirements are relaxed in the future (by, for example, no longer supporting older software with those limitations).

If the first point (direct use of JWTs by third-party services) becomes compelling, the authentication handler could create and inject a JWT into the HTTP request to those services without otherwise changing the model.

The primary driver for using opaque tokens rather than JWTs is length, which in turn is driven by the requirement to support HTTP Basic authentication. If all uses of HTTP Basic authentication can be shifted to token authentication and that requirement dropped, the decision to use opaque tokens rather than JWTs should be revisited (but revocation would need to be addressed).

5.2.2 Token scope¶

JWTs natively carry their scope as one of their claims. For opaque bearer tokens, the scope will be stored as part of the corresponding session entry. In either case, tokens can be restricted to specific scopes.

The token used for web browser authentication and stored in the session cookie should have unlimited scope. The strongest authentication of the user is via the web browser, and the user should be able to take whatever actions they are allowed to do via that path.

More limited scopes are therefore for user-created API tokens, and possibly for auto-created API tokens for automatic token delegation (such as for the notebook environment). The details of automated token delegation are intentionally left open in this design, apart from ensuring it will be possible to support them, since the requirements and use cases are not yet clear.

For user-created API tokens, there will be a balance between the security benefit of more restricted-use tokens and the UI complexity of giving the user a lot of options when creating a token. The current design intention is to identify the use cases where a user would need a separate API token and provide a UI to create a token for that specific purpose, possibly with an advanced user escape hatch that would allow the user to make a more unrestricted choice of token scopes. This balance will be discussed in more detail in future documents as the requirements become clearer.

5.2.3 Federated authentication¶

The simplest design for API authentication, and indeed for the entire authentication system, is for all protected applications to run within the same Kubernetes cluster. Each separate Kubernetes cluster (the summit, for example) would have its own independent instantiation of this authentication system, without any cross-realm authentication.

This may not be practical or desirable in practice. If API credentials issued from one cluster need to be usable to authenticate to services in a different cluster, and particularly if services need to accept credentials from multiple issuers, opaque tokens are no longer desirable. An opaque token does not contain the necessary information to tell the recipient which authentication system to use to verify it or retrieve the authentication and authorization information it represents. This requirement would therefore argue for the reintroduction of JWTs instead of opaque tokens, which unfortunately reintroduces the token length concern or requires the system issue multiple token types depending on the use case. (This would also require the user know to ask for different token types depending on the use case.)

Different deployments of the Science Platform are likely to have different sets of authorized users, which would have to be taken into account for cross-cluster authentication and authorization.

It’s not yet clear whether cross-cluster federated authentication will be necessary. Until that’s been established, it is not included as part of this design. However, this point will have to be revisited as the requirements become clearer.

5.3 Web browser authentication¶

Web browser authentication is somewhat simpler. An unauthenticated web browser will be redirected for initial authentication following the OpenID Connect protocol. Upon return from the OpenID Connect provider (CILogon), the user’s identity is mapped to a local identity for the Science Platform and a new session and corresponding opaque bearer token created for that identity.

Rather than returning that bearer token to the user as in the API example, the bearer token will instead be stored in a cookie. Unlike with API tokens, these tokens should have an expiration set, and the user redirected to re-authenticate when the token expires.

Use of cookies prompts another choice: Should the token be stored in a session cookie or in a cookie with an expiration set to match the token? Session cookies are slightly more secure because they are not persisted to disk on the client and are deleted when the user closes their browser. They have the drawback of therefore sometimes requiring more frequent reauthentication. The authentication system will also need to store other information that should be transient and thus in a session cookie, such as CSRF tokens, and it’s convenient to use the same cookie storage protocol for the token.

The initial proposal is to store the token in a session cookie alongside other session information, encrypted in a key specific to that installation of the Science Platform. If this requires users to re-authenticate too frequently, this decision can be easily revisited.

This design ties the scope of a browser session to a single domain. All web-accessible components of an installation of the Rubin Science Platform will need to be visible under the same domain so that they can see the browser session cookie. Cross-domain browser authentication would add significant complexity, so hopefully this design constraint will be workable. If not, the authentication system described here may also have to be an OpenID Connect provider that can serve satellite authentication systems in other domains.

5.4 Group membership¶

There are two approaches to handling authorization when using JWTs: Embed authorization information such as group membership into the JWT, or have the JWT provide only identity and look up group membership in a separate authorization service as needed.

Whether to include authorization information in authentication credentials is a never-ending argument in security. There are advantages and disadvantages either way. Advantages to including authorization information in the credentials:

Authorization decisions can be made without requests to an additional service, which can reduce latency and loosen the coupling between the authorization service and the services consuming its information. (For example, they can be run in separate clusters or even at separate sites.)

A credential is self-describing and doesn’t require queries to another service. A credential is also frozen; its properties do not change over its lifetime.

It’s easy to create credentials that carry the identity of a user but do not have all of that user’s permissions.

Advantages to keeping authorization information out of credentials:

Authorization information can change independently from the credentials. This is particularly important for long-lived credentials that act on behalf of a user who may be dynamically added to or removed from groups. They can continue to use the same API tokens, for example, and don’t have to replace them all with new ones with a refreshed group list.

Authorization can be revoked without revoking the credentials. When the authorization information is embedded in the credential, and that credential is stolen, there is no easy way to keep it from continuing to work without some form of revocation protocol. Some credentials have no standard revocation protocol (JWTs, for instance), and even when such a protocol exists, it’s often poorly-implemented or unwieldy.

Authorization decisions can use data that is too complex to easily serialize into the authentication credentials.

Tokens are smaller (although still not small enough to use with HTTP Basic authentication).

For the Science Platform, it is important to be able to change authorization information (particularly group information) without asking people to log out, log in again, and replace their tokens. There will likely be significant use of ad hoc groups and interactive correction of group membership, which should be as smooth for the user as possible. The requirements also call for non-expiring API tokens, and requiring them to be reissued when group membership changes would be disruptive.

This design therefore uses authentication-only credentials. This would continue to be the case even if the opaque tokens were replaced with JWTs.

The credential is an opaque token that maps to an underlying session, which can be independently invalidated if needed for security reasons. Group information will be dynamically queried on request. Individual tokens may carry all the groups and permissions of the user, or may be limited to a subset via that session information.

Authorization and group information will likely to be cached for scaling reasons, so changes will not be immediate. Cache lifetime and thus delay before an authorization update takes effect is a trade-off that will be set dynamically based on experience, but something on the order of ten minutes seems likely.

This approach will result in more traffic to the authentication and authorization services. Given the expected volume of HTTP requests to the Science Platform, the required level of scaling should be easy to meet with a combination of caching and horizontal scaling of those services.

Group membership and GIDs for file system access from the Notebook Aspect will likely need to be set on launch of the notebook container to work correctly with NFS, so as a special exception to the ability to dynamically update groups, Notebook Aspect containers will probably need to be relaunched to pick up group changes for file system access.

5.5 File storage¶

5.5.1 Storage backends¶

None of the options for POSIX file storage are very appealing. It would be tempting to make do with only an object store, but the UI for astronomers would be poor and it wouldn’t support the expected environment for the Notebook Aspect. Simulating a POSIX file system on top of an object store is technically possible, but those types of translation layers tend to be rife with edge-case bugs. The simplest solution is therefore to use a native POSIX file system.

Of the available options, NFS is the most common and the best understood. Any anticipated Rubin Data Facility is likely to be able to provide NFS in some way.

Unfortunately, the standard NFS authorization mechanism is UIDs and GIDs asserted by trusted clients. The NFS protocol supports Kerberos, but this would add a great deal of complexity to the Notebook Aspect and other services that need to use the file system, and server implementations are not widely available and are challenging to run. For example, Google Filestore (useful for prototyping and test installations) supports NFSv3, but not Kerberos.

Other possible file systems (such as cluster file systems like GPFS or Lustre) are generally not available as standard services in cloud environments, which are used for prototyping and testing and which ideally should match the Data Facility environment.

AFS and related technologies such as AuriStor deserve some separate discussion. AFS-based file systems are uniquely able to expose the same file system to the user’s local machine and to the Notebook Aspect, Portal Aspect, and API services. This neatly solves the problem of synchronizing files from a user’s machine to their running notebook, the portal, and their collaborators, which would be a significant benefit. Unfortunately, there are several obstacles:

The user would need to run a client (including a kernel module). Those clients can lag behind operating system releases and require support to install and debug (which Rubin Observatory is not in a position to provide).

AFS-based file systems are similarly not available as standard services in cloud environments.

Running an AFS file system is a non-trivial commitment of ongoing support resources and may not be readily within the capabilities of the Rubin Data Facility.

AFS-based file systems generally assume Kerberos-based authentication mechanisms, which would require adding the complexity of Kerberos authentication to the Notebook Aspect and possibly to user systems. (It may be possible to avoid this via AuriStor, which supports a much wider range of authentication options.)

While having native file system support on the user’s system would be extremely powerful, and AuriStor has some interesting capabilities such as using Ceph as its backing store, supporting a custom file system client on the user’s system is probably not sufficiently user-friendly as a default option.

None of the other options seem sufficiently compelling over the availability and well-understood features of NFSv3.

5.5.2 Remote access to storage¶

This leaves the question of how to provide file system access from a user’s local device. Since the user population is expected to be widely distributed and Rubin Observatory will have limited ability to provide local support, there is a strong bias towards using some mechanism that is natively supported by the user’s operating system. Unfortunately, this limits the available solutions to nearly the empty set. WebDAV has native integration with macOS and integration with the Finder, and uses HTTP Basic, which can support bearer tokens using the mechanism described in 4.2 API authentication. It is therefore the current design baseline.

SSH could also be used, either via scp/sftp or through (at the user’s choice) something more advanced such as SSHFS, which allows a remote file system to appear to be a local file system. It is harder to support in this authentication model and is not part of the initial proposal. However, it could be supported by, most likely, adding a way for a user to register an SSH key to tie it to their account, and then providing an SSH server that allows sftp access to the user’s file system spaces.

A file sync and share solution, such as CERN’s CERNBox based on ownCloud or an equivalent commercial product such as Google Drive, is another option. This shares with a distributed file system such as AFS the property that a user can edit files directly on their local system and see the changes reflected automatically within the Science Platform without requiring additional steps.

A commercial sync and share product would introduce a new authentication and authorization component: user authentication to the commercial product. A self-hosted solution such as ownCloud would probably be able to reuse the API authentication approach. Either way, there would need to be an agent in the Science Platform to synchronize files from the sync and share storage into the user’s home directory as visible from the Notebook Aspect. It would have to use whatever authentication credentials are supported by the sync and share system.

At the moment, no firm decisions can be made about the authentication and authorization approach until a file system approach has been chosen, but any of these approaches should be supportable by this framework.

6 Open questions¶

Will the Science Platform need to provide shared relational database storage to users with authorization rules that they can control (for example, allowing specific collaborators to access some of their tables)?

Will the Science Platform need to provide an object store to users with authorization rules that they can control (for example, allowing access to their objects to specific collaborators).

How do we handle changes in institutional affiliation? Suppose, for instance, a user has access via the University of Washington, and has also configured GitHub as an authentication provider because that’s more convenient for them. Now suppose the user’s affiliation with the University of Washington ends. If the user continues to authenticate via GitHub, how do we know to update their access control information based on that change of affiliation?

Will there be a need for cross-cluster API authentication? In other words, is there a need for API credentials issued from an authentication system living in one Kubernetes cluster to be used to access services in a different Kubernetes cluster?

Can all of the web-accessible components of the Rubin Science Platform be deployed under a single domain, or will there be a need for cross-domain web authentication?